THE UNMUTUAL PRISONER ARTICLE ARCHIVE

RENDEZVOUS:

"THE HANGING OF ALFRED WADHAM"

Discovery & Review

by Tom Mayer

©2016

It is always worth celebrating when a forgotten appearance from Patrick McGoohan's

early career unexpectedly resurfaces. In this case, the title in question involves

two famous authors, a successful film producer and, most intriguingly, one of

the future directors of The Prisoner -- all of whom came together for one episode

of an obscure television series that went under four different titles and was

part of a unique US/UK collaboration. That this production still exists is noteworthy

in itself; even better, it was recently made available for viewing and study,

thus allowing for an opportunity to analyze an appearance of McGoohan's which

has gone unseen for almost sixty years. As I was fortunate to have seen this

episode, I thought some research into its history was in order. Little did I

know it would lead me on a journey through the intriguing shared worlds of ghost

stories and 1950s anthology television.

THE ORIGINAL STORY

It actually begins as far back as the 1920s with English author/playwright E.F. Benson. Best remembered today for Dodo and the Mapp and Lucia series, he also wrote an impressive amount of ghost and suspense stories. One of these was published in 1929 when another writer of the supernatural, Lady Cynthia Asquith (The Spring House, This Mortal Coil), edited an anthology of fifteen suspense stories called Shudders. These "shivery" tales were "selected not for brutal violence or bloodthirstiness, but for cleverness in the treatment of the weird, of strange turns in human frailties or weaknesses and untoward doings."1 Benson was represented with his tale "The Hanging of Alfred Wadham."

The story -- spoilers ahead -- concerns a priest, Father Denys Hanbury, who is conflicted upon learning that a condemned man is actually innocent of a murder he is to be hanged for. The real killer has confessed to the crime and cruelly taunts the priest, knowing the latter cannot break the Seal of Confession by turning him in. The wrong man (Alfred Wadham) is eventually hanged, and Hanbury is soon haunted by what he thinks is Wadham's ghost. The final scene reveals the apparition to be a devil which has taken Wadham's form to psychologically torment the priest. Reciting a prayer and holding up a crucifix, Hanbury succeeds in sending the demon back to oblivion. Save for the occasional appearance in "ghost story" anthologies, this tale was largely forgotten for thirty years until another famous author was entertaining ideas for a new television series.

GHOST TIME

Before Roald Dahl wrote James and The Giant Peach and Charlie and The Chocolate Factory in the 1960s, he enjoyed success writing for television. By 1958, he had contributed scripts to programs such as Suspense, Alfred Hitchcock Presents, and Phillip Morris Playhouse, and as a result, was eager to produce a series of his own. Luckily, he had a connection within the industry to whom he could pitch ideas. Edwin H. Knopf, brother of literary magnate Alfred A. Knopf (Dahl's publisher), had already been successful in motion pictures since the 1930s, producing or directing such titles as The Law and The Lady, Lili, The Glass Slipper and Santa Fe Trail. "I went to [Knopf] with the idea that we should do a television series together of nothing but ghost stories," Dahl recalled. "I pointed out that no one had done this before . . . there existed a whole world of ghost stories to choose from and that it wouldn't be difficult to come up with a stunning batch of tales." 2

Knopf agreed to produce the series and Dahl set about choosing some two dozen stories which would comprise an entire season's worth of episodes. It was here that he discovered "The Hanging of Alfred Wadham." He was so impressed with Benson's tale that he selected it to be the pilot episode of the new show, which he had christened Ghost Time. "The pilot is important in any series," he maintained. "It has to be good. This is the film that is shown to the network bosses . . . and after looking at it they either turn thumbs-up or thumbs-down on putting up the millions that are required to make the whole series . . . [it] gives a fair idea of what the other twenty-three episodes will be like."

A cast and crew were assembled, including Patrick McGoohan, William Ingram, Paul Massie and Laurence Naismith. In a notable indication of things to come, the episode was shot by prolific UK television director Pat Jackson who, eight years later, would end up being chosen by McGoohan to direct no fewer than four episodes of The Prisoner. Interior scenes for "Alfred Wadham" were filmed at Elstree Studios with exterior location work done in and around London. An introduction by writer/actor Emlyn Williams (The Corn Is Green) was added, and a print was subsequently struck and sent to Hollywood for the studio to preview. Overall, Dahl was pleased, considering the project "awfully good." "We couldn't go wrong," he thought. “The big boys figured that a series of chilling ghost stories flashed on to the television screens from coast to coast in the winter evenings when it was pitch dark outside would give the entire nation creeps . . . [it] was a heady prospect."

Unfortunately, things did not go as planned. Due to the conservative nature of television in the 1950s, the subject matter of a Catholic priest contemplating breaking the Seal of Confession was deemed too risky by the network. Dahl was told that "the sight of it on the television screen would be guaranteed to inflame the hearts of millions of Catholics across the United States," while the reaction of those within the industry was hardly positive. "The advertising men and the television bosses who saw the pilot were apoplectic," he lamented. "They threw it out and refused to have anything more to do with our splendid ghost series venture." Dahl apparently never got over the experience. In fact, he still harbored resentment that some 25 years later, he couldn't justify including the original story in his 1983 collection of ghost tales -- he even admitted that he had forgotten who had directed and starred in it!

RENDEZVOUS

Edwin Knopf, on the other hand, was hardly discouraged. Realizing that "Alfred Wadham" was too good to waste, he simply transferred it to the roster of another series he was producing at the time -- Rendezvous. It was part of a wave of anthology programs that were abundant on television in the 50s and 60s, along with You Are There, The Vise, Armchair Theater, Thriller and, of course, The Twilight Zone and The Outer Limits. The hook of the series was that each episode transported the viewer to a different country where that week's story took place. Character actor Charles Drake (Winchester '73, Valley of The Dolls) starred as John Burden, who appeared in most of episodes as one of the main characters, but in others served more like a host, showing up in "bookend" scenes at the beginning and end of each story.

Rendezvous had an unusual production history. Knopf had inherited the show from producer Howard Erskine, who had already filmed thirteen episodes for the American market. Using his CBS Films company to strike a deal with Associated-Rediffusion in the UK, Knopf produced the remaining installments in England. As a result, Dahl and Pat Jackson, who were based the UK, ended up writing and directing additional episodes for the series, thus explaining how “Alfred Wadham” was easily transferred from the aborted Ghost Time to Rendezvous. Obviously, minor changes had to be made for the episode to better fit the style of the new series. All references to Ghost Time were dropped, while Emlyn Williams' original introduction was replaced with a new "wraparound" sequence featuring John Burden meeting with a monk to set up the story.

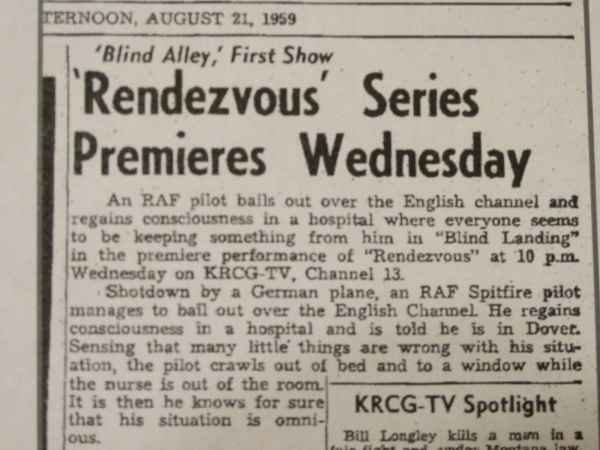

Being made-for-syndication, Rendezvous aired at scattered times in various markets, sometimes under different titles. Most of the U.S. saw it as Rendezvous, while on the west coast it was known as Schilling Playhouse, and in the east as Rheingold Theatre '59 (due to the popularity of one of its New York sponsors, Rheingold Beer). The program aired sporadically in the U.S. from 1959 to 1961 where it was hyped as an "anthology of great works by great writers" that "brings you a new experience in dramatic fare each week. Suspense, comedy, love, fantasy and shock are the ingredients of the series with one aspect featured in each [episode]." The pilot, "Mama Pontani" (also directed by Jackson), aired as early as February 1959 with Variety stating, "despite its faults, [it] had an adult offbeat approach" and "definitely departs from the simple action-adventure syndication rut . . . [it] surely bears further watching."4

Today, detailed information on the show is scarce. It is unclear how many episodes were eventually produced (sources differ between 25, 39 and 41), or whether all of them aired in the U.S.5 "Alfred Wadham" does not appear to be among the ones that did, but "The Executioner," another episode McGoohan starred in, was screened at least on the east coast in March 1960. As for the UK, the entire series appears to have aired under the Rendezvous title. Ultimately, the show made little impact and was almost immediately forgotten, with critics today remembering it as "utterly undistinguished.” 6

Rendezvous and Ghost Time were Edwin Knopf's only forays into producing television, but Dahl continued in the medium with some success. His predilection for showcasing the macabre was such that within two years, he produced, wrote and hosted his own suspense series called Way Out. Running a mere fourteen episodes on CBS in the summer of 1961, it was often aired back-to-back with The Twilight Zone due to their similar styles. Yet, despite receiving positive reviews when it premiered, Way Out was quickly cancelled due to low ratings. Today it is considered "one of the missing gems of early TV anthologies," with historians arguing that "it deserves to be resurrected. Much more sinister than The Twilight Zone, much more sophisticated than One Step Beyond, Way Out presents nasty little stories about nasty little people, with a very wicked touch . . . the writing is wonderful [and if] it ever pops up, catch it, but only if you like being spooked." 7

DISCOVERY & SCREENING

While conducting research on McGoohan's career, I was thrilled to discover -- through a simple internet search -- that a 16mm print of "Alfred Wadham" was held in the collection of the UCLA Film & Television Archive. I emailed the university and the staff responded, kindly granting me permission to visit any time within the next few months to view the episode. I hadn't been to Los Angeles in over five years, so this was a perfect excuse to spend a week in California, while catching a rare appearance of McGoohan's in the process.

My third day in town, Friday, October 28, 2016, dawned cloudy with light rain -- an unusual scenario for Los Angeles. At least the gloom helped get me in the mood for viewing what promised to be a spooky suspense story (appropriately, it was also the start of Halloween weekend). Leaving my hotel in Venice Beach, I successfully navigated the traffic on LaBrea and Wilshire Boulevards, and by the time I arrived at UCLA, the drizzle had given way to gorgeous blue sky -- typical for L.A., I thought, where even the rainy days end up sunny and clear!

I made my way across the picturesque campus to the Powell Library, where I found the Media Lab on the second floor. After signing in, I was shown to a small screening room containing a table, chairs and a wall-mounted TV set. Before leaving, the librarian handed me a remote and said there was no time limit -- I could watch the program as many times as I wanted. Anticipation mounting, I set out my notebook, dimmed the lights, and pressed PLAY . . .

THE EPISODE

The title sequence features the credits keyed over a spinning globe as the camera zooms into the south of England, since the story takes place in London (one wonders if all the episodes began like this, or if each opening was altered to focus on part of the globe where that week’s story was set). We open with John Burden (Charles Drake) visiting a Benedictine monk, "an expert on the subject of devils," to discuss the conflict between good and evil. The monk states that "devils dominate us; make us their servants," yet there also exist "armies of angels" to fight these devils, thus protecting humanity. The monk then recounts the story of a priest, Father Denys Hanbury (Patrick McGoohan), who had such an experience concerning this conflict.

The scene flashes back to a prison cell where Hanbury is hearing the confession of prisoner Alfred Wadham (William Ingram). Wadham has been convicted through circumstantial and physical evidence of murdering his employer, Gerald Selfe, and is scheduled to hang the following morning. Yet after confessing his other sins to the priest, Wadham continues to maintain his innocence regarding Selfe's murder. It is obvious that Hanbury doesn't believe him, but he maintains his clerical objectiveness by advising the prisoner to pray for forgiveness and to prepare for his eventual fate.

Later that evening in his rectory, Hanbury receives a visit from a troubled man named Horace Kennion (Paul Massie) who begs the priest to hear him out. In a tortured confession, Kennion breaks down revealing that he killed Selfe after the two men got into a fight during a card game. Afterward, Kennion cleaned up the crime scene and planted false evidence that he knew would incriminate Wadham. A look of shock and relief registers on Hanbury's face as he reaches for the phone, intending to have Kennion arrested and Wadham freed. But Kennion suddenly changes his demeanor, becoming smug and scheming. He taunts Hanbury revealing that a weight is now off his conscience, and that the priest is powerless to tell the police (or anyone else) about this admission of guilt. If Hanbury does, Kennion vindictively reminds him, he will be breaking the sacred Seal of Confession that all priests must adhere to. Kennion also reveals that he has long disliked Hanbury after the priest once said that "no decent man would consort with [him]." As revenge, Kennion decided "it would be pleasant to see [Hanbury] in the most awful hole," (i.e., suffering from agonizing torment).

At a loss, Hanbury visits his superior, the Cardinal (Laurence Naismith), and without going into specifics, reveals the dilemma in which he finds himself. The Cardinal confirms that the two of them are virtually powerless -- they are indeed bound by the confessional seal. He suggests that a visit to the Home Secretary might help since the clock is ticking down to Wadham's execution, and Hanbury agrees. "And whatever you suffer, my son," the Cardinal advises Hanbury as he leaves, "be sure that you are suffering not from having done wrong, but from having done right." Unfortunately, the meeting with the Home Secretary goes nowhere as Father Denys learns again that, without details, proof or names, the hanging will proceed as scheduled.

After a commercial break, the story resumes the next morning in the jail as Hanbury implores Wadham to receive final absolution. The priest is obviously distraught over the impending tragedy and Wadham notices the change. "You're sure I didn't do it," he realizes. "What changed your mind so suddenly? Now you're actually begging me to receive [absolution].” Hanbury's sadness is palpable as he stoically replies, "I simply had a change of heart." Still claiming that he is innocent, Wadham puts up a brief struggle with the prison guards as they lead him away. The shot then dissolves to a notice announcing that his execution has been carried out.

Despondent, Hanbury leaves the prison on his bicycle and, after stopping in traffic at a red light, is shocked to see Wadham staring at him from across the street! The apparition immediately vanishes, but Hanbury is shaken enough that he almost runs into an elderly cafe owner on the sidewalk. She notices his disturbed state and invites him inside for a cup of tea. He sits at a table in an attempt to relax, but as he looks out a nearby window, he sees Wadham staring in at him accusingly. The priest jumps up with a start, causing the cafe customers to regard him as if he were mad (of course, they do not see Wadham).

Thanks to a sympathetic cab driver, Hanbury receives a free ride home. As he is about to enter his house, the front door slowly and ominously swings open by itself to reveal Wadham standing inside. Hanbury now realizes that something must be done. He turns and quickly walks across the street to his church. With the ghost trailing him, Hanbury makes his way inside, kneels in front of the altar and begins to pray. After a moment of silence, he senses the apparition behind him and rises to face it.

Father Denys at last realizes the true nature of what is before him. He surmises that since Wadham received absolution before his execution, his soul must have ascended into heaven. Therefore, this manifestation cannot be Wadham, but rather a devil appearing in his form to cause torment. Father Denys summons his courage and loudly recites a prayer to cast the apparition back to where it came. Church bells ring and organ music rises on the soundtrack as the devil stares at the priest with an accusing, tortured look. Slowly, the specter fades away leaving Hanbury alone in the church contemplating his victory over the evil presence.

A final scene returns us to Burden asking the Monk how he was able to recount this story without breaking the Seal of Confession. The Monk reveals that Kennion had committed suicide after having been tortured by his conscience, but not before leaving behind a note containing his confession of Selfe's murder -- thus resulting in the exoneration of Alfred Wadham. The closing credits then roll with the camera zooming out from the Rendezvous globe, now surrounded along the bottom by an eerie mist.

ANALYSIS

Having seen the episode, I can confirm it is a brilliantly produced effort. Dahl improves on Benson's story by adding new scenes that flesh out the narrative and characters. This keeps the plot moving so the viewer is never bored at any point. One advantage is the Wadham character appearing in an actual role rather than existing "offscreen" as in the story. We can better sympathize with his plight since we know him as a real person. Overall, the episode is a straightforward drama until the revelation of Wadham's ghost and the exorcism sequence. These supernatural themes seem almost an afterthought -- the implications of Hanbury's torment constitute enough drama in itself (although this criticism could be leveled at the original story as well).

I assumed the episode would be a videotaped play, but instead, it is a single-camera filmed production that appears to have had a large budget. It looks and feels more like a feature film, benefiting from elaborate sets and exterior locations. Stephen Dade's camera work boasts an excellent balance of wide shots and close-ups that help avoid a stagy theatrical look. Interestingly, the episode has an unintended "period" atmosphere to it -- so much so, that a viewer could be forgiven for assuming that it takes place in the 1920s (or earlier). The numerous linking shots of McGoohan riding his bike in London traffic to and from the jail remind us that the episode is happening in the (1950s) present-day rather than the earlier setting of the original story.

Pat Jackson's direction is flawless as he brings out confident performances from the cast and utilizes the photography and locations to their potential. At one point, he films a lengthy, unbroken take during the scene of Kennion's confession. The shot begins with Hanbury on the phone discussing Wadham's case as Kennion arrives, is shown inside by a maid, recounts his meeting with Selfe and confesses to the killing. On the word "murder," Jackson finally cuts away to a close-up of Hanbury's shocked reaction. It's an impressive example of economical filmmaking that conveys drama and tension while retaining the theatrical feel of live television within a filmed production. Jackson also works in a clever "bookend" effect at both ends of the episode. The opening shot shows the monk entering the church and later, after his conversation with Burden, we see him leave the building and walk across a courtyard in the final scene.

The image of Wadham's ghost following Hanbury around is an eerie sight, with his manacled hands and head cocked at a grotesque angle (suggesting the recent hanging). The scene of him standing in a crowd on the street staring at Hanbury is quite disturbing, as is the moment the priest arrives home to find the ghost waiting for him just inside his front door. Yet these initial sightings are merely a prelude to a brilliant special-effect shot of Hanbury entering the empty church (alone, we think). In a high-angle view from behind the altar, we see a set of double doors at the far end of the hall. Hanbury enters through one door and walks toward the camera down the right side of the main aisle (screen left). A moment later, the opposite door opens by itself, and the ghost of Wadham slowly materializes halfway down the left side of the aisle, walking a few feet behind McGoohan. It is a beautifully executed split-screen effect, both chilling and impressive.

McGoohan, a year away from filming his first episodes of Danger Man, gives a remarkable performance. His acting runs the gamut from despondent and driven to conflicted and haunted. He pulls off the climactic exorcism scene particularly well, his voice quaking with emotion and echoing throughout the church as he summons his will to banish the ghost before him. Throughout the episode, he speaks with a slight Irish lilt, while the image of him in his clerical robes neatly prefigures his role four years later in Dr. Syn: The Scarecrow of Romney Marsh. Any viewers familiar with his other 1950s TV roles can easily place this appearance alongside "This Day In Fear" and "The Man Out There," which are also well-made and engrossing to watch.

There are fine performances from the supporting cast as well. Paul Massie is suitably calculating and smug as Kennion, while William Ingram is convincingly terrified as the condemned prisoner, then terrifying as the demon ghost. Notably, this cast was either already, or would soon be, quite familiar with McGoohan. Massie had appeared with him a year earlier in the film High Tide At Noon, while Naismith and Ingram would guest star in two future episodes of Danger Man -- "The Blue Veil" and "The Hunting Party," respectively (with the latter being a "Wadham" reunion of sorts, since it was directed by Pat Jackson).

The copy of the episode at UCLA was on a DVD burned from a VHS dub of the original black & white 16mm reel. Commercials were cut out, with a brief "Sponsor's Message" title card appearing during the breaks. Total running-time, without ads, was 26mins 16sec. The picture quality was a bit "soft," but definitely was not from a Kinescope (where a video image is filmed off a TV monitor). The episode appears to have been filmed in 35mm widescreen, since the image completely filled the 16x9 screen upon which I viewed it. The characters and sets were properly framed within each shot with no stretching or squeezing of the image. Broadcast copies were most likely struck from this print then "panned-&-scanned" for over-the-air screenings. For all we know, this is the only copy in existence -- thankfully, it looks fantastic for its age and will clean up nicely for a DVD release.

Unfortunately, its brief running time will work against it being issued on its own disc. It would probably need to be included in some sort of "umbrella" collection of anthology shows (similar to the way assorted episodes of You Are There were issued on DVD in 2004). As of this writing, it is unclear if every episode of Rendezvous still exists, so a "Complete Series" set is a slim possibility. Nevertheless, "The Hanging of Alfred Wadham" is a superb example of 1950s anthology TV at its finest. While remaining (indefinitely for now) an unfairly forgotten gem of television drama, it is also a telling reminder of the numerous lost treasures still out there waiting to be discovered and enjoyed again.

Thanks to Mark Quigley and the staff of the UCLA Film & Television Archive

for arranging a screening of this episode.

1. "Novels

of The Day." Sydney (Australia) Morning Herald, January 10, 1930

2. All Dahl quotes from the introduction to Roald Dahl's Book of Ghost Stories,

Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1983.

3. "'Rendezvous' Series Premieres Wednesday." Jefferson City [Missouri]

Post-Tribune, August 21, 1959.

4. Variety. "Syndicated Review: Rendezvous." February 25, 1959.

5. Internet Movie Database and Classic TV Archive website entries for Rendezvous

and Schilling Playhouse.

6. Castleman, Harry and Walter J. Podrazik. Harry and Wally's Favorite TV Shows.

Prentice Hall, 1989.

7. Castleman & Podrazik.

Because the entries for this teleplay on both the Internet Movie Database and

Classic TV Archive websites are either incomplete or incorrect, here for the

first time, are the episode’s credits as they appear onscreen (with the

characters' names added for completeness):

RENDEZVOUS

An Edwin H. Knopf Production

Starring

Charles Drake

as John Burden

"The Hanging of Alfred Wadham"

Written

by

Roald Dahl

Based

On a Story by

E.F. Benson

With

Patrick McGoohan ... Father Denys Hanbury

William Ingram ... Alfred Wadham

Paul Massie ... Horace Kennion

Laurence Naismith ... The Cardinal

Directed

by

Pat Jackson

Produced

by

Edwin H. Knopf

Associate

Producer

Denis O'Dell

Director

of Photography

Stephen Dade B.S.C.

Music

Direction ... Bretton Byrd

Art Direction ... Elven Webb

Assistant Director ... Buddy Booth

Editor ... Maurice Rootes

Dubbing Editor ... Terry Poulton

Camera Operator ... Gerry Massey Collier

Produced

for Associated-Rediffusion

by Rapallo Pictures

© MCMLIX (1959)