THE UNMUTUAL PRISONER ARTICLE ARCHIVE

TOTAL

IMMERSION PART 1:

THE HISTORY OF PATRICK McGOOHAN'S FORGOTTEN DIRECTORIAL EFFORT, CATCH MY SOUL

(a.k.a. SANTA FE SATAN)

By Tom Mayer

©2013

What does the creator and star of The Prisoner have in common with the opening

act at Woodstock, Elvis Presley's stunt-double, the Manson Family murders, the

creator of Shindig!, Jerry Lee Lewis, Kurt Russell's ex-wife, the deserts of

New Mexico and Shakespearean tragedy? As bizarre as it may seem, these disparate

sources all joined together in a 1974 rock-opera version of Othello that was

eagerly anticipated at the time of its release, ignored almost as soon as it

premiered, then forgotten and eventually presumed lost.

It also marked Patrick McGoohan's only effort as a feature film director.

A true pop-cultural curiosity, the film Catch My Soul is now impossible to see today, due to the complete lack of any home video releases or TV screenings during the last four decades. In this age of deluxe DVD and Blu-Ray sets, and online streaming of the latest films and TV shows, the average viewer may be forgiven for assuming that everything ever filmed is now out there within easy access. Even productions that have not been officially released are usually available via unofficial copies that circulate among fans and collectors. The total unavailability of any one production can be a bit surprising. For something as bizarre and curious as Catch My Soul, its absence makes it all the more intriguing. McGoohan's biographer, Rupert Booth, appropriately describes the film as "frustratingly elusive."1

Internet searches reveal little information, apart from cast listings and questions about its availability. Even more surprising is that not one frame of footage has so far surfaced in the digital era. With no online clips or unofficial copies available, anyone interested in the film would be understandably curious about what has happened to it. While it is known that a large percentage of titles from the silent era have been lost or destroyed, what causes a production from as "recently" as 1974 to go missing? After all, we're not dealing with a lost title from 1924! Obviously, this film's absence is a bigger issue than originally thought, and worthy of investigation.

With 2012-15 marking the 40th anniversary of the filming and various releases of Catch My Soul, the time is long overdue for an examination of this obscure production. The story behind it is a tale of strange twists and odd connections that spans over seventy years. Additionally, in piecing together the bizarre story of the film's production and disappearance, I discovered there also exists the amazing possibility of its eventual reemergence. . .

THE BEGINNING

By 1972, Patrick McGoohan's career was in a period of transition. The final episode of The Prisoner aired in early-1968, causing a short-lived controversy that forced him and his family to go into hiding in Wales until the trouble died down. Within a few months, McGoohan and his family left the U.K., staying in Switzerland for a time at his in-laws. He obviously wanted a rest and a change of scenery after two decades of working in theater, film and television. During this time, he reduced his workload, appearing in only two films, The Moonshine War (1970) and Mary, Queen of Scots (1971).

Eventually, the McGoohans moved again and settled in, of all places, Santa Fe, New Mexico. It's a bit puzzling as to why the family chose this location. Perhaps Patrick wanted to be as far away from show-business as possible? Regardless, he might have been content for the time being, but it wasn't long until show-business found its way back to him.

"I was living in New Mexico at the time," he recalled, "taking a sabbatical of sorts, painting, scribbling poetry, stuff like that, and looking at the scenery." 2 It was during this idyll that McGoohan was approached by a neighbor ("No point mentioning his name," he quipped years later). This person, another recent U.K. transplant, had heard that McGoohan was now living in the area, and wanted him to direct an ambitious motion picture project. McGoohan was understandably hesitant -- who was this man who had the courage to interrupt his relaxation and ask him to drop everything to direct a film in the deserts of New Mexico?

THE PRODUCER

The man’s name was Jack Good. He may not be well-remembered today, but he was one of the major talents behind-the-scenes of early rock & roll in the United Kingdom. Born in London in 1931, he first aspired to be an actor, but instead worked his way through the entertainment industry until, by the late fifties, he was producing the music programs Oh Boy! and Wham! Through these shows, Good was pivotal in launching the careers of such U.K. singers as Billy Fury, Marty Wilde and Cliff Richard, along with introducing American rockers Eddie Cochran and Gene Vincent to British audiences. It wouldn't be a stretch to label Good the British counterpart of Dick Clark during this time.

By the mid-sixties, Good had moved to the United States, where he produced another notable contribution to pop-culture: the music show Shindig! Airing from 1964-66 on ABC, the program featured live performances of the Beach Boys, the Rolling Stones, the Who and countless others. Decades later, TV historians consider Shindig to be "a goldmine of pre-MTV clips of the best of rock." 3

Good continued to act whenever he got the chance, guest-starring on such TV shows as That Girl, The Andy Griffith Show, Hogan's Heroes and The Monkees. The latter appearance led to Good producing the now-obscure special, 33 1/3 Revolutions Per Monkee. Apparently, he never lost his fondness for rock & roll shows. However, it was on That Girl where Good made an important connection with the program's distributor, Metromedia, a company that would help him finance a certain film project years later.

In the meantime, Shindig ended in 1966, and Good decided to go ahead with a project he'd been considering for years -- something that involved his love for Shakespeare's Othello. The idea had evolved over decades, stemming from an experience he had as long ago as 1940. "[It] really began when I was a child of nine," he told The Los Angeles Times. "[It] was something of a revelation, going to see Othello. I didn't even fully understand what was going on on the stage, but it had an impact on my life. It made all the difference." 4

The experience was what inspired Good to become an actor, specifically so he could play Othello. He first performed the role at age 15, and again later, while he was at Oxford. By the time he was successful in music and television, he had dreamed up a modern retelling of the Bard's tragedy. "I first started thinking about [Catch My Soul] in 1958," he recalled. "It's a collage of various ideas combining Shakespeare and rock. It's funny how Shakespeare, back in 1604, could come up with a story that is so contemporary today." 5

For those who don't remember their high-school Shakespeare (or for those who intentionally blocked it out), here's a brief summary of the play in question:

Othello, a black general in the Venetian army, has recently married his white wife, Desdemona. Othello's ensign, Iago, is furious that Othello recently passed him over for promotion to lieutenant, instead promoting Michael Cassio. Consumed with rage and jealously, Iago embarks on an elaborate scheme of revenge to destroy Othello's marriage. Using Cassio as his unsuspecting pawn, Iago convinces Othello of Desdemona's assumed infidelity. This leads Othello, slowly driven to madness, to murder his wife.

The title of Good's planned production came from a line spoken by the main character. After Desdemona and Iago's wife, Emilia, exit a scene, Othello speaks with affectionate sarcasm about his wife:

Excellent wretch! Perdition

catch my soul

But I do love thee! And when I love thee not,

Chaos is come again. [Act 3. Sc. 3]

FROM STAGE TO SCREEN

Good first envisioned Catch My Soul as a stage play. The original version played in Los Angeles for three months in 1968, with William Marshall as Othello and, surprisingly, "The Killer" himself, Jerry Lee Lewis, as Iago. The show garnered mixed reviews, with one critic saying it was "like a pop music concert encircling a shredded edition of the great tragedy." However, the production design was recognized as "visually stunning," while Lewis's piano-pounding performance was well-received. Credit was given to Good for his vision, in that the play was "a creative effort, juices flow, and there's life involved, and with all its limitations, there is something there." 6

After the play wrapped, Good made the first of several changes to the script. Not far from where he was living in Los Angeles at the time, one of the most infamous crimes of the 1960s occurred -- the Tate/LaBianca murders, perpetrated by Charles Manson and his followers. The event stuck in Good's mind, and eventually influenced the changes in Catch My Soul. "[I] tried to picture in my mind what the murderer was like," he explained. "I figured he was probably a failed rock musician who played drums or something. And I figured he was probably into the occult and saw himself as a devil figure. And on those assumptions, I created a 'Tribe of Hell' to serve as Iago's followers. . ." 7

With this change in place, Good moved the production to the U.K. in 1969. The new cast included P.P. Arnold, P.J. Proby and, this time, Good himself as Othello. Additionally, Lance LeGault took over the role of Iago from Jerry Lee Lewis. For the next three years, this version played in several cities, including Birmingham, Manchester, Oxford and London. One reviewer remembered it as "exuberant and imaginative . . . presenting a finely balanced mixture of original Shakespearean dialogue and pulsating sixties rock music." 8

After it closed in early-1972, Good then decided to produce a film version. By this time, he had enough connections and experience within the industry to launch such an ambitious project. One of his contacts was producer Charles Fries from Metromedia, who had seen the play in London. The company had recently helped distribute the horror film, Tales From The Crypt, and they were interested in producing another film project from scratch. 9

More importantly, the rock-musical or "rock-opera" had taken root in the pop-cultural landscape by this time. Jesus Christ Superstar, Godspell, Hair, and Tommy had all been successful on stage and screen. Coming along when it did, Catch My Soul made sense from a financial standpoint. To Fries, and the others in charge at Metromedia, it seemed like a safe investment.

Good was understandably enthusiastic. "Although I had been spiritually preparing to do the movie for 12 years," he mused, "in just three weeks it all began falling into place." 10 He and Fries assembled a cast and crew, and moved the production to New Mexico, where Good was now living. The story was transplanted to a hippie commune in the desert, while Othello was changed from an army general into a traveling "preacher-man." Iago underwent the most dramatic change -- he was no longer a jealous man bent on revenge, but now the devil incarnate, driving a black bus and ruling his "Tribe of Hell." Good also scrapped the original score, and proceeded to create an entirely new soundtrack for the film version.

THE DIRECTOR

As writer and producer, Good was planning to direct the film as well. However, he may have had doubts about his abilities, or it might have been too much of a workload. He looked around for someone to take over the creative helm, and noticed that McGoohan was now living in Santa Fe. Perhaps Good's recollections of Secret Agent and The Prisoner were still vivid, and he remembered that McGoohan was just as much of a talent behind the scenes as he was on camera. That this man was now living in Santa Fe was too good an opportunity to pass up.

McGoohan described the awkward scene that led to his involvement in the film. "Jack Good was going to direct it . . . and he got cold feet at the last moment," he remembered. "And eight days before it shot, he asked me if I'd do it. And as the movie was so weird and I was up there brooding about other things, I thought it'd be nice to be around cameras again. So, I said 'yes' . . ." 11 The project must have appealed to McGoohan, who was probably growing restless after not having worked for many months.

Good agreed about McGoohan's reluctance, but with a bit more candor. "It took me weeks of argument before I could even persuade Patrick to direct this picture," he told the U.K. Sun. "He's a genius, but a difficult son-of-a-bitch. I love the man, but his indifference to his trappings of success would exasperate a saint." 12

Regardless, Good was enthusiastic about the many similarities he shared with his film's new director, all of which he must have interpreted as a good omen. "Now, it happens that Patrick McGoohan and I both had recently moved to Santa Fe," he explained. "We both were interested in working on films, we were looking for houses, we each had a wife and three daughters, were both eccentric Catholics, and had played Othello." Then he emphasized, "We both have a G-O-O in the middle of our names! And we are so totally opposite that we are abrasive in a way that is entirely complimentary . . ." 13

This "complimentary abrasiveness" might have seemed an advantage at first, but Good perhaps did not consider that things could just as easily go bad in the long run -- as would be played out in the eventual fate of the film.

Another similarity that Good overlooked was how both men were endeavoring to create successful careers on the other side of the Atlantic from where they had started. That these two major figures of 1960s U.K. pop-culture should meet up in the 1970s American southwest, and collaborate on such a timely production, is at the least, a notable coincidence.

Additionally, this project was McGoohan's third association with a variation on Othello within a decade. The first was the 1962 jazz film All Night Long, in which he played the Iago role of Johnny Cousin, a scheming drummer who attempts to break up the marriage of two friends in order to persuade the wife to join his band. The second was the 1967 Prisoner episode, "Hammer Into Anvil." Again in an Iago-like role, McGoohan's character of No.6 slowly drives the current No.2 mad through paranoia and trickery in order to avenge the death of a young woman.

CAST & CREW

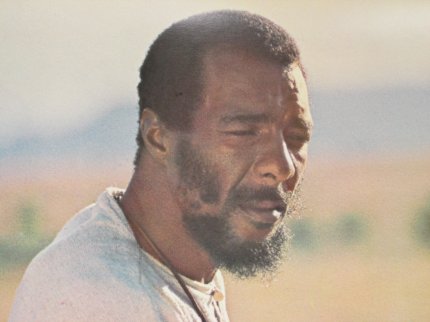

By the time McGoohan agreed to direct, the film had already been cast with a notable assortment of musicians and character actors. Folk singer Richie Havens was starring as Othello. In 1969, his place in pop-culture history was forever immortalized when he appeared as the opening act at the legendary Woodstock Festival. In 1971, he scored his only U.S. Top 40 hit, an excellent cover of The Beatles' "Here Comes The Sun." This recording showcases his deep, resonant voice, and unique open-tuning acoustic guitar style. In the following decades, Havens continued to record and tour constantly, his connection with Woodstock forever linking him to the optimism and ideals of the 1960s. He sadly died in April of 2013, during the writing of this article.

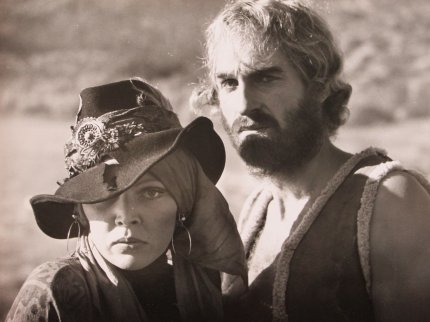

Lance LeGault was still on board as Iago, carrying over from the London stage version. He began his career as a stunt double for Elvis Presley in the 1960s, and also played percussion in the King's famous '68 Comeback Special. LeGault later carved out a remarkable career as a character actor, appearing in many American television series such as Knight Rider, Magnum P.I., Quantum Leap and the Babylon 5 spinoff, Crusade. His most memorable role was Colonel Decker in the 1980s action series The A-Team. With his imposing presence and unforgettable voice, he was always well-cast as military characters or authoritative figures. In 1972, however, Jack Good thought him well-suited to play the devil incarnate in Catch My Soul.

Singer Tony Joe White played Michael Cassio. White is the best known performer of "swamp rock" -- an often irresistible combination of country, blues and funk. The songs of Creedence Clearwater Revival are good examples, but White's 1969 classic, "Polk Salad Annie" is the definitive offering. White also recorded the original version of "Rainy Night In Georgia", which was a big hit for Brook Benton in 1970.

He remained puzzled as to how he ended up in Catch My Soul. "Lord knows, I don't know," he told Sounds magazine in 1973. "Jack Good chose me about two years ago. [McGoohan] called me down to Santa Fe to talk so that we could do it, and I went in there and I said, 'Look I'm just a musician, man, I've never acted, I don't know how to act and I don't ever learned to be.' He said, 'I don't want somebody who knows how to act.' So me and him hit it off right from the start." 14 Despite White's reservations about his acting, his skills as a musician were never in doubt -- Good entrusted him with writing and performing the majority of the film's new soundtrack.

Season Hubley starred as the ill-fated Desdemona. She was virtually beginning her career in Hollywood at this time, with few credits to her name. Prior to filming Catch My Soul, she co-starred with Jeff Bridges and Rod Steiger in Lolly-Madonna XXX (a.k.a. The Lolly-Madonna War), another rare film unavailable on video or DVD. She later married actor Kurt Russell after the two starred in a 1979 TV-movie about Elvis Presley, with Russell in the title role and Hubley as the King's wife, Priscilla. She also appeared in Russell's cult-classic Escape From New York in 1981.

Susan Tyrrell was cast as the scheming Emilia, in cahoots with her husband Iago. In 1971, she appeared in an Oscar-nominated role in John Huston's Fat City, later turning up in such varied films as Andy Warhol's Bad, The Forbidden Zone and Powder. She was no stranger to television either, guest-starring in many series throughout the years, including Mr. Novak, Wings and Open All Night. She continued to act well into the 2000s, even after contracting a rare blood disease that resulted in her legs being amputated below the knees. Coincidentally, she and Lance LeGault died within three months of each other in the summer of 2012.

Singers Delaney and Bonnie Bramlett rounded out the cast. They were best known for their jam band "Delaney & Bonnie and Friends." Over the years, they performed with many rock and soul luminaries including George Harrison, the Allman Brothers, Rita Coolidge, and Eric Clapton. Interestingly, one of Delaney's early gigs in 1965 was as a member of the Shindogs, the house band on Shindig! This was obviously where he first met Jack Good, and the two kept in touch until Good started casting Catch My Soul seven years later.

There was notable talent behind-the-scenes as well. Cinematographer Conrad L. Hall was at the peak of his career, having filmed Cool Hand Luke, Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid, Fat City (with Susan Tyrrell) and Electra Glide In Blue in the five years prior to working on Catch My Soul. One of his more memorable later efforts was 1999's American Beauty. Editor Richard A. Harris, who worked mainly on TV-movies around this time, eventually teamed up with director James Cameron to edit his 1990s blockbusters Terminator 2, True Lies and Titanic.

THE PRODUCTION

Filming began in September 1972 just north of Santa Fe, near the towns of Espanola

and Pojoaque. The production was centered around two main locations: the San

Ildefonso Indian pueblo, and the Bert Brown Ranch which was located off Highway

285. 15 A 28-day location shoot was scheduled, with a

budget of $750,000 (approximately $4,165,000 or £2,681,000 in 2013) 16.

Adjusted for inflation, this is still an extremely small price tag for a feature

film, given that a major studio production today can average $20-50 million.

Catch My Soul was, without a doubt, very much an "indie" production.

Barbara Burman, writing for the Santa Fe New Mexican, was enthusiastic about

the proceedings. "For a few glorious weeks," she reported, "Santa

Fe has been near the top of the world -- the Rock 'n' Roll World, that is. Probably

the most exciting event in popular music has been unfolding in the hills of

northern New Mexico, where some of the biggest names in rock music have been

filming Catch My Soul." Good revealed to her why northern New Mexico in

particular was chosen. "It's primitive, unencumbered by side issues,"

he explained. "The place is so strong." Burman was equally taken with

the idea of hearing "350 year-old lines sounding out from adobe walls and

spoken by actors in blue jeans and boots [causing one] to wonder at the universal

timelessness of the Bard." 17

The cast and crew were apparently welcomed by the area residents. The film's

director made a good impression as well: ". . . Patrick McGoohan, is also

a new Santa Fean," Burman wrote, "and with his mellifluous voice and

dignified manner, [he] has charmed those local people who have met him."

An invaluable source of information on the film's production was a remarkable

article by Gregg Kilday for the Los Angeles Times. Kilday was present on the

set for several days, interviewing many of the people involved. He painted a

vivid picture of what the production must have been like, particularly during

the desert nights "where the arc lamps cast gargantuan shadows on the pallid

mesa walls, and the cold night air threatens to swallow the small band of filmmakers."

18 During one "clear, star-choked" desert night,

with the temperature hovering in the 30s, and the crew huddled around campfires,

Kilday witnessed a revealing moment of McGoohan interacting with Richie Havens

and Susan Tyrrell. The lead actor was having trouble with his dialogue during

a wedding speech:

Havens . . . blows his line again. It is the 13th take of what is to be

the beginning of a sequence celebrating Othello's marriage to Desdemona. "...Let

the wedding feast begin. Everyone rejoice in the Lord."

Richie stubbornly blows Take 14 as his words drift away on the chilly winds.

"Richie," cajoles Patrick McGoohan, former Secret Agent and director

of "Catch My Soul", "remember Woodstock? Remember what it was

like? Can we see some of that?"

Some takes later, the line still unperfected, McGoohan calls cut, print. Brooding,

he wanders over to Susan Tyrrell, a wild-spirited young actress who is playing

Iago's Emilia.

"How you feelin', me dahlin'?" he asks, a buoyant Irish lilt cutting

through the night's dark spirits. "High and mighty?"

Susan smiles knowingly. "Oh, you say such wicked things," she says.

"I had a long talk with Richie today," she offers in encouragement.

"He hates my guts, you know," the director answers sharply. "But

that's all right with me." Together the two step out of the circle of light

into the neighboring darkness. 19

Kilday didn't elaborate on what alienated Havens and McGoohan from each other. The latter was known to polarize his colleagues into two camps -- those who got along with him famously, and those who couldn't stand him. Perhaps Havens' relative inexperience as an actor was frustrating to McGoohan, who always expected his co-workers to be well-rehearsed and not waste time in retakes.

If Havens didn't get along

with McGoohan, Tony Joe White, on the other hand, came away with great memories.

"You know Patrick is a funky guy, really a soulful cat," he told Sounds

magazine. "He has just a knack for making people like myself feel really

good. Like I've never even been in front of a camera, and he would come up to

me later and say to me, 'That was really great. It was really good, and the

only time I'm going to say anything to you is when you're not being yourself'.

He didn't try to make me anything." 20

Susan Tyrrell added her unique perspective on Good, Havens and McGoohan. "I'll

tell you what to look for here," she told Kilday. "Take Jack, if he

were boiled down in a little vial, the vial would be full of . . . wizardry.

And if Richie were boiled down, that vial would be full of . . . bliss. But

Patrick, oh, he's a soul mate, Patrick's vial would contain only . . . pain.

All those little vials, so potent! All those images they make! Extraordinary!"

21

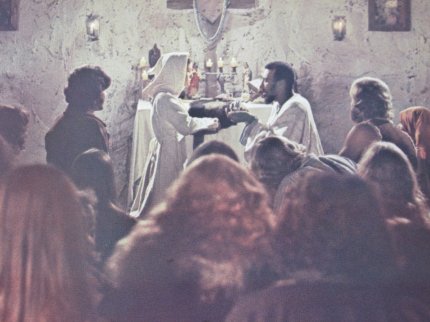

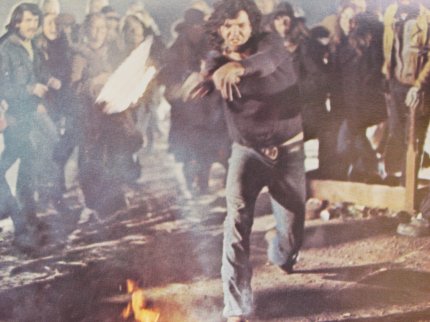

The aforementioned wedding celebration sequence required the presence of a large

crowd, so approximately 150 "bona-fide hippies" were recruited from

the "marijuana-scented" streets of Santa Fe. The extras were bused

to the filming location, and upon arrival, were let loose and told to party

to a performance by Delaney & Bonnie. The celebration got a little too rowdy,

with several crew members wondering if things had gone too far. Afterward, Kilday

witnessed McGoohan tensely pacing back and forth, most likely wondering to himself

"[why he was] here on this frozen reservation, directing an army of hopped-up

freaks in this bastardized tale from Shakespeare." 22

Another valuable insight to the production came from Santa Fe resident Douglas Magnus. He worked on the film, first as an assistant to the set-dresser, then later as an unofficial photographer. He and a colleague were planning to document the production for Rolling Stone magazine, but their project was suddenly cancelled, and Barbara Burman's article was instead chosen to be the official coverage. Regardless, Magnus ended up taking numerous photos throughout the filming.

He remembered a somber atmosphere surrounding the shoot. Santa Fe usually has nice weather, but the fall of 1972 suffered from cloudy, cold, and rainy conditions that created a dark mood on the set. "[It] was an amazing circus of characters and events," Magnus recalled. "Not all of it felt good . . . [the] idealism of the 60's was fading into something else. The production wasn’t working. People were confused. The weather was bad. But, a lot of local people got work, including me, which I needed badly . . ." 23

Magnus shared his impressions of McGoohan, whom he observed many times from a distance during filming. He remembered the director as a "brooding presence" who, thanks to an ever-present bottle of J&B Scotch, always seemed to be "well intoxicated." He also noted that McGoohan's onscreen demeanor closely matched the way he was in real life. 24 Magnus also recalled a near-disaster one night when he was helping the special-effects crew. The story called for Iago to start a fire inside a church built by Othello. The crew had been maintaining a controlled blaze inside the building when photographer Conrad Hall demanded more smoke for his shot. The crew increased the amount of fuel to the blaze until it spread out of control and engulfed the building. Magnus ran in with a bucket of water to try and douse the flames. He had barely made it back outside when the roof suddenly caved in. Hall later told him that when he saw the roof give way, he thought Magnus was a dead man. 25

Being a musical, the successful

performing and recording of the soundtrack was a priority. Billboard magazine

reported on the unique way the music was produced for the film. Each actor's

vocals were performed live during filming, in order to avoid the slick, overproduced

image of big-budget musicals. "We had decided in advance that the film

would have absolutely no lip-synching to pre-recorded songs," Good said.

"It always looks so phony, especially when you have a real singer rather

than an actor." Additionally, the instrumentation was limited to one or

two acoustic guitars, to keep the performances as realistic as possible. "[We'd]

never have somebody singing alone in the desert with an entire orchestra coming

in from empty air," Good added. "This [music] is much more believable

with just a few instruments." 26

During production breaks, the musicians in the cast found time to perform at

various shows. Havens appeared at a political gathering at the Albuquerque airport.

Actor Dennis Hopper had organized a rally for then-democratic vice-presidential

candidate Sargent Shriver, and Havens performed a few songs. 27

Additionally, Good arranged his own concert on October 29 to show his appreciation

for the local residents. The show featured performances from all the musicians

in the film, and the ticket sales raised several thousand dollars for the local

Cristo Rey School, which Good's children were attending at the time. 28

The rest of filming was eventually completed on schedule, and the production

wrapped. "All last week, the cast and crew of Catch My Soul were packing,"

the local paper reported. "[Now], only traces remain of the neo-Shakespearean

village that existed briefly just north of here . . . [but] the touch of the

Bard has been updated, set to music and brought to northern New Mexico. And

that deathless touch will be remembered." 29

With that, everyone involved with the film scattered. McGoohan got to work assembling

the footage with editor Richard A. Harris. Eventually, they polished it to a

cut that McGoohan was happy with, then he too, departed -- no doubt returning

to his painting and poetry. Meanwhile, White and LeGault reconvened at Gold

Star Studios in Hollywood to record the songs again in polished versions for

the soundtrack LP. Havens didn't join them though -- he had already recorded

his songs on location during breaks in filming. He didn't want to be anywhere

near the West Coast after having a premonition that California was going to

drop into the ocean following an earthquake. 30

It was during this period that the first of many things to go awry with the

film occurred. Jack Good underwent a personal change or revelation in his life

that inspired him to reassemble the cast and crew and shoot several minutes

of additional footage. He then took McGoohan's cut of the film and re-edited

it to incorporate the new sequences. The original director wasn't happy when

he found out.

"I met [Good] about five or six months later," McGoohan recalled,

"and he says, 'God told me I had to put more about Him in it' . . . Well,

he got religion, I mean, incredible, a bolt from on high and so on, he shot

extra stuff and put about 15 minutes of this garbage in it." 31

McGoohan wanted nothing to do with the film after this. He even asked for his

name to be removed from the credits, but his request was ignored.

RELEASE &

REVIEWS

Assuming McGoohan finished his cut in early-1973, and Good informed him of the

new version "five or six months later," then the film would have been

ready for release by late-summer. This is confirmed in a syndicated article

that announced, "Metromedia Studio is so confident it has a super-hit on

its hands with Catch My Soul, it's scheduling a full-blown Hollywood premiere

to unveil that cinema rock-opera version of Othello in September." 32

This was an admirable effort on the part of the producers to launch the film

with as much fanfare as possible. However, during the research for this article,

no evidence was found that the premiere ever took place. It is unknown what

led to the event being cancelled, but it is indicative of the many poor decisions

made concerning the project, as well as the bad luck that would continue to

plague it for much of its known existence.

While the movie languished in unreleased limbo, one of the first reviews of

it appeared in a U.K. film magazine. It is unclear how critic Simon Greig was

able to see the film before its release. He might have been an American correspondent

for the magazine, who attended a press screening in New York or Hollywood; or

perhaps a print of the film had already made it to the U.K. Regardless, Greig

said that he "approached the viewing of McGoohan's first attempt at feature

film directing with some measure of excitement," having fondly remembered

both the stage version of Catch My Soul, and several episodes of The Prisoner,

which he felt "McGoohan had directed in fine, taut style." Yet Greig

ended up disappointed with the film, saying that the script, "like some

skeletal Elizabethan relic, falls flat on its uninspired face," due to

"the absence of sufficiently motivating dialogue, [in which] the characters

are reduced to the level of unconvincing, two-dimensional cardboard cut-outs."

He criticized the musical format as Good's attempt to "paper over the cracks

of a brittle script by relying too heavily on extra background music."

Also, while he liked McGoohan's "frequently imaginative direction,"

and LeGault's "magnetic performance," Greig thought Havens' great

musical talent ironically "spotlights his painful lack of acting experience."

He ended the review, wondering "why on earth they didn't call it, Kitsch

My Soul, a more fitting choice for a title." 33

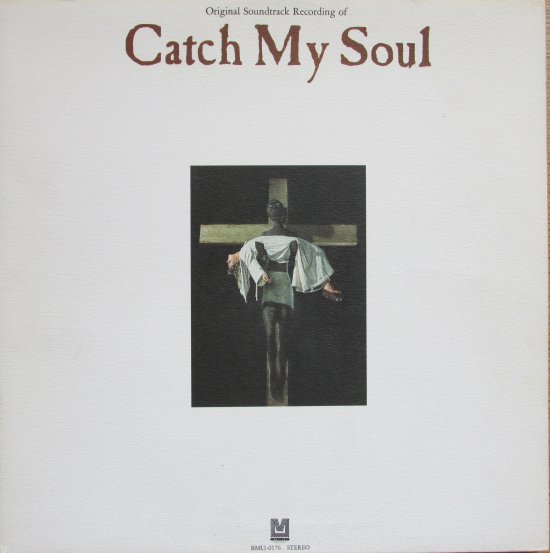

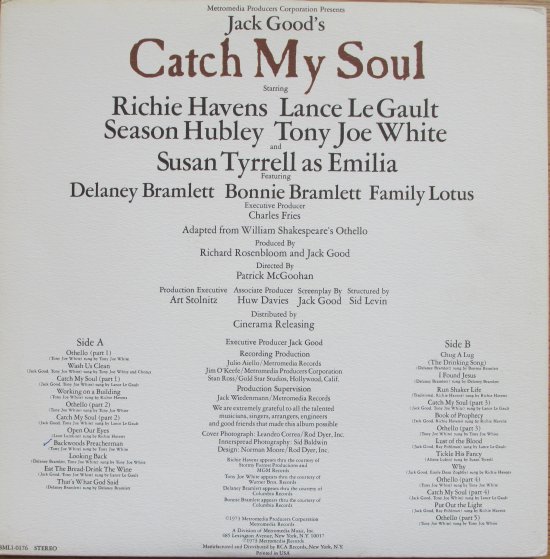

The soundtrack LP was finished, and released circa late-1973. It appeared in the U.S. on Metromedia Records (BML 1-0176), and in the U.K. on RCA (RS 1004). The record was housed in a gatefold sleeve that inside featured several images from the film. Also included was a large tan booklet that contained the lyrics and a scene-by-scene description of the plot, to help put the songs in context for listeners who hadn't seen the film.

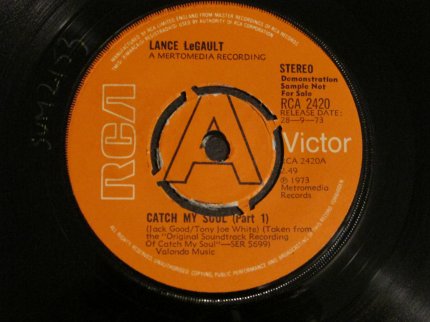

Two attempts were made in the U.K. to score hit singles from the album. "Catch

My Soul Pt. 1" by Lance LeGault backed with "Tickle His Fancy"

by Susan Tyrrell was released on 45rpm as RCA 2420. Either someone thought the

title track was worthy of being a hit, or maybe LeGault saw a chance to further

his singing career alongside his acting. The other release was Delaney Bramlett's

"That's What God Said" b/w "I Found Jesus" on CBS 1914.

Not surprisingly, both 45's sank without a trace.

As a result of these musical releases, another early review appeared, focusing

on just the soundtrack. Pierre-Rene Noth of The Milwaukee Journal cautioned

readers that, "It's risky to evaluate a film by the soundtrack alone."

(Little did he know that researchers would be attempting to do that very thing

some forty years in the future!) He said, "the visual aspects of this one

are going to have a lot to overcome, mainly some bad lyrics," yet he praised

Havens as "one of the few rock voices whose sound has never harmed any

song. His deep, quiet omnipotent tones are especially well-suited to sounding

godlike." Noth felt the music was "lively at times, [but] never hints

at the sort of catchiness that made Jesus Christ Superstar so powerful a vehicle."

He negatively concluded, "However the film turns out, one can't help but

be glad that Shakespeare isn't around to hear this. He had a strong sense of

humor, but not strong enough to take this." 34 It

was hardly a good sign that the film had yet to be released, but had already

garnered two negative reviews.

During this time, Metromedia joined with Cinerama to help with the film's distribution.

The latter company is best remembered for their widescreen projection process

that was used for many films in the 1960's -- most notably, Stanley Kubrick's

2001: A Space Odyssey. By the early-seventies, the company had apparently moved

into distribution and promotion.

Cinerama's backing was what the film needed. After half a year in limbo (and

a full sixteen months after its filming), Catch My Soul finally premiered in

New York City on Friday, March 22, 1974. It played in approximately sixteen

theaters in the tri-state area, from suburban New Jersey (Paramus), to upstate-New

York (New Paltz), to even McGoohan's birthplace of Queens. (With over a dozen

copies of the film in existence at this one time in the NYC area, it's hard

to believe that all of them have since gone missing.)

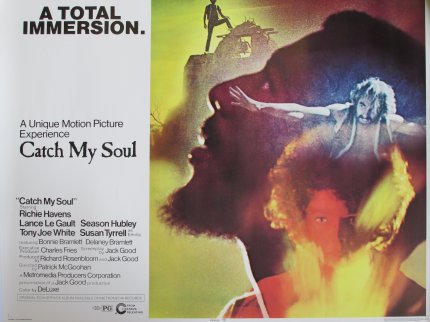

The New York Times featured a large advertisement, with a banner proclaiming

the film "A Total Immersion" (a phrase taken from the lyrics of LeGault's

title track). The screening was hyped as "A Unique Motion Picture Experience"

playing in select "Catch My Soul Showcase Theaters!" These slogans

were obvious marketing attempts to make the premiere sound as exciting as possible.

That same week in the Times, the old New York-area department store, Korvettes,

carried an ad for the soundtrack album. Sharing company with the latest records

by Roy Clark and Steely Dan, the LP was on sale for only $3.99!

Things didn't go well, however. New York Times critic Vincent Canby panned the

film, beginning his review with George Bernard Shaw's quote about Othello: "'Tested

by the brain, it is ridiculous; tested by the ear, it is sublime.' Tested by

almost any organ you might want to mention, Catch My Soul is pricelessly funny

though seldom meaning to be." Canby liked the music, calling Havens "as

credible an Othello as it's possible to be under the nervy circumstances,"

but added, "It's the hybrid plot and dialogue that keep one in what is

genteelly called stitches." He wrapped up with the advice, "Forget

the movie and get the soundtrack album." 35 (Apparently,

the entire world did exactly that, considering that the LP is now one of the

few tangible traces of the film left out there.)

In New York Magazine, Judith Crist simply called the film "an embarrassment"

that "joins bastard Shakespeare with 'man' and 'dig it' jargon." She

trashed the script and performances, but gave points to Jack Good, who "one

should note in fairness, says he began working on this twelve years ago, predating

Jesus Christ Superstar and the Satanist fashion." 36

The film was advertised in the Times for only two more days, with the size of

the ad growing smaller each day. By Monday March 25, there was no sign that

it was still playing. If it bombed like that in New York, apparently the studio

realized there wasn't much hope for it anywhere else. Any remaining plans for

a full national release were probably scrapped at this point.

Catch My Soul then played sporadically around the country, if at all. Searching

the microfilm for The Los Angeles Times and The Atlanta Constitution from March

and April of the same period, no evidence was found that the film played in

either city. Strangely, on March 30, the Atlanta paper incorrectly reprinted

Canby's New York Times article as a theater review, with the title "Catch

My Soul Is Funny." Apparently, someone confused the movie with the original

play, and mistook Canby's negative sarcasm as a positive statement -- all for

a film that wasn't playing in Atlanta anyway! 37 The big

surprise however, was that there was no screening in Los Angeles. It's possible

that the film might have been shown there later in 1974, but if not, it's a

telling clue of either the poor handling by Metromedia, or of the producers

having pulled the film soon after the negative reviews in New York.

The film managed to open in Boston on May 12, where critic Kevin Kelly ripped

it apart in a Boston Globe review: "What we have here is Shakespeare compounded

with Jesus Christ Superstar and my-oh-my, on the final day of judgment, Catch

My Soul is going to have a lot to atone for." He thought the premise of

the entire film was "not only confused, [but] also absurd", calling

Good's screenplay "a crock", and McGoohan's direction "heavy

with mood [and] melodramatic shtick." He wrapped up with the warning, "I'd

avoid it, if I were you, like the plague." 38

In the June 1974 issue of the obscure PTA Magazine, Ethel Whitehorn said the

film "begins well, with poetically photographed open spaces and rapt young

faces filled with religious fervor," but things go downhill when "the

solemnity of the subject begins to overwhelm everyone involved, and the film

escalates into hysterical singing and shouting duels between [Othello and Iago].

As the decibels mount, the warmth and humanity lessen, and frenzy takes over."

In discussing the cast, she amusingly called Tyrrell's Emilia "a slut with

a steel-covered heart of gold." For this publication of the Parent-Teachers

Association, Whitehorn had to conclude each review by stating how the film in

question was suitable for various age groups. She said adults would like it,

"if interested in new ideas, however much a shambles." For adolescents,

"the music by name singers may appeal." And for children, she finished

with an emphatic "No." 39

In the midst of this negative onslaught, a positive review emerged in, of all

places, the industry standard, Variety. Calling it a film "which devotees

of this type of divertissement no doubt will find right up their alley,"

the magazine praised Havens’ performance as one of "quiet intensity,

gradually building to raving killer," and LeGault's turn as one of "masterful

style." The review added that Hubley "scores nicely as Desdemona,"

along with Tyrrell and White "both delivering sound performances."

The highest praise went to the behind-the-scenes talent: "Patrick McGoohan's

taut direction catches the full spirit and Conrad Hall's beautiful color photography

is one of the most interesting attributes of the film. Richard Harris' tight

editing also is a definite plus." 40

This one positive review in a sea of negativity was obviously not enough to

help. With audiences not knowing or caring about the film's existence, a handful

of stinging reviews, and a shockingly short theatrical run, the ill-fated venture

never had a chance to establish itself. It was gone almost as quickly as it

appeared.

FALL OUT

The film then embarked on a winding road to obscurity. Metromedia made attempts to recoup as much money as it could from the failed property. It was re-released a year later in 1975, with a new title, Santa Fe Satan. The change was probably to fool anyone familiar with the failure of Catch My Soul. Those in charge must have assumed that a different title would lure viewers into theaters under the assumption they were about to see something "new." Plus, with 1973's The Exorcist still fresh in viewers' minds, the word "Satan" in the title might have been a ploy to make the film sound like another tale of demonic possession. Copies of the re-release were available in 35mm and 16mm formats, presumably to increase the number of rentals that could be screened in large theaters or in small gatherings (such as college film societies).

Drive-in theaters were also targeted. It was on this circuit that the film finally premiered in New Mexico in 1975 at an Albuquerque drive-in, about an hour's journey south of the place of its creation. It was part of a double-feature with, of all things, Slaughterhouse Five. The local viewers apparently thought little of the film that was shot in their midst. As an audience member recalled years later, when Slaughterhouse Five ended and Santa Fe Satan began, "all but about six cars left -- and most of them were either drunk or making out." 41

The re-release obviously had less of an impact than the original version. Evidence was found of only two other documented screenings under the Santa Fe Satan title. The first was at a film series sponsored by the Beaux Arts Gallery in Pinellas Park, Florida in April 1976; 42 while the second was at the Original Folk Music Festival in Modesto, California in March 1977. 43 One wonders what these audiences of folk musicians and artists thought of the bizarre film! No doubt, it was met with as much indifference as at the Albuquerque drive-in. How the film was chosen to be screened at these gatherings is puzzling. It was perhaps an easy acquisition on the part of the organizers, since prints were readily available. They were probably also looking for something "hip" with a musical atmosphere.

It is here that the trail of the film's existence begins to grow cold. One of last official references to it appears in the 1982 book Feature Films On 8mm, 16mm and Videotape by James Limbacher. In the "S" section, three lines of stark type list Santa Fe Satan as being available on a 16mm color print. 44 Intriguingly, New Line Cinema was now listed as the distributor, having taken over from Cinerama. This was already the seventh edition of the book, so presumably, the film had been included in earlier printings as far back as 1975-76. It is not known how much longer into the eighties that the film was still listed as being available. After that, nothing. Jack Good's rock-opera completely disappears from the pop-cultural landscape.

Occasionally a brief reference to the film would surface, proving that it wasn't forgotten. In 1983, a California resident was arguing with her friends about the whether the film actually existed. She eventually wrote to the entertainment editor of her local newspaper. "Richie Havens once starred in a musical version of Othello," she asked. "My friends say I'm crazy, so can you verify this with the title and year?"

"You're not crazy," the Merced Sun-Star responded. "You're just one of the few people who probably ever saw Catch My Soul, Jack Good's 1974 rock adaptation of Shakespeare's tragedy." 45 Interestingly, Merced, California is a mere 40 miles from Modesto. This neatly explains where the person in question saw the film -- at the 1977 Folk Music Festival screening! It's amazing how, within six years, the film's existence was already being questioned.

By the early-1980s, the home video revolution was underway, with the first VCRs appearing in households. Why Santa Fe Satan was not released on VHS or Betamax at this time is a mystery. Perhaps the stigma of its 1974 failure was still fresh in the minds of Metromedia executives. Perhaps the film had been forgotten by those in a position to release it on home video. It's also possible that an attempt was made at a video release, but all prints were lost by then.

Because of its unavailability, the film never had a chance to attract a cult following years later. Other widely-recognized bombs such as Plan 9 From Outer Space (1959), Xanadu (1980) and The Room (2003) have all maintained their reputations over time, simply by being available on home video for new generations of viewers to search out. More importantly, Catch My Soul missed out on a proper re-evaluation of its merits. If curious viewers had been able to give it another chance years later, its original negative reputation might have been changed.

METROMEDIA

The story behind the film's studio is full of surprises. Metromedia formed from the remnants of the old DuMont television network of the 1950s. By the seventies, they were one of the biggest television conglomerates in the U.S., owning many stations across the country. They also created and distributed programs for the networks and first-run syndication. Hit shows such as That Girl and Too Close For Comfort; sitcom oddities such as Dusty's Trail and Small Wonder; Alan Thicke's late-night talk show bomb, Thicke Of The Night; and even many Jacques Cousteau documentaries all bore the production stamp of Metromedia over the years. 46 The company even ran its own record label with RCA during the late-sixties and early-seventies. Among several dozen singles and LPs, the two biggest hits it scored were "Color Him Father" by The Winstons in 1969, and "I'd Like To Teach The World To Sing" by the Hillside Singers in 1972. The Catch My Soul soundtrack was one of the last records the label released before it disappeared, circa-1974. 47

In 1986, the company bought out the holdings of Orion Pictures when the latter went bankrupt. By 1997, Metromedia itself was failing, and in an attempt to save themselves, they sold their properties to 20th Century Fox. Surprisingly, Metromedia then went into, of all places, the food industry, where they owned Bennigans and Steak & Ale restaurants for about a decade. In 2008, both restaurants went bankrupt, and with that disappeared the last traces of the Metromedia empire, save for a few radio stations still around today. 48 It was an appropriately odd finale to a strange continuum that, at one point, included Jack Good's rock-opera.

Apart from its television ownership, Tales From the Crypt and Catch My Soul were Metromedia's only ventures into feature filmmaking. After the 1997 buy-out, it's safe to assume that Fox owns every videotape and reel of film that Metromedia ever produced. While it’s tempting to believe that a pristine negative (or even the unedited rushes!) of Catch My Soul might be contained somewhere in the Fox vaults, it’s highly unlikely.

FAILURE

The film's failure can be explained by a number of factors. Besides the poor handling by its parent company, the timing of its release should be considered. After Jesus Christ Superstar, Godspell, Tommy, etc., audiences and critics were probably sick of rock-operas by the mid-1970s. Another title added to this long list was no doubt met with indifference. Ironically though, Catch My Soul pre-dated them all by way of its 1968 stage version -- Jack Good was ahead of the game in that respect.

One must also take into account the other films that were vying for audiences' attention in the spring of 1974: Badlands, The Sting, The Conversation, Blazing Saddles, Sleeper, and The Last Detail, just to name a few. The rest of that year would see the release of everything from Chinatown to The Towering Inferno to The Godfather Part 2. With so many choices appealing to casual filmgoers, it's no wonder the release of Catch My Soul went unnoticed.

Another criticism that can be leveled at the film was in the handling of its source material. In her excellent book, The Friendly Shakespeare, Norrie Epstein says about Othello, "[its] emotions are so highly pitched, its plot so improbable, its action so compressed, that without the right touch it can easily collapse into melodrama or farce." 49 This aligns perfectly with complaints from reviewers about the film being "uninspired, "two-dimensional" and "absurd." In this case, an attempt to shoehorn the classic tragedy into a musical just couldn't work.

Interestingly, the precariousness of the film's existence seemed evident from the moment of its creation. Along with Doug Magnus’ recollections of a “dark mood” on the set, a prophetic observation was made by Gregg Kilday amid the "madness" of the film's production. He eerily predicted, ". . . if just the tiniest bit of all the surrounding turmoil finds its way through the celluloid to the screen, Catch My Soul could rock with an unsettling energy uncommon to the movies. But if all the contending tensions simply cancel each other out, the work would unroll routinely, another predictable stillbirth." 50

The film was Jack Good's last credited effort as producer, save for an odd 1976 TV-variety special starring Mary Tyler Moore. Titled Mary's Incredible Dream, the hour-long production combined musical numbers with surreal dream sequences. The offering has gained a reputation as a bizarre failure that attempted to expand the limits of 1970s variety specials. The show (surprise!) has never been rerun or released on home video. 51 In a way, it seems a strangely fitting end for Good's career.

LEGACY

Opinions of Catch My Soul today are mixed, with the majority being negative. The ratio of good-to-bad reviews is virtually the same as it was in 1974. At the positive end, TV Guide's website gives the film two-and-a-half stars out of four. They state this "odd rock adaptation of Othello somehow works," adding that "[it] could easily have degenerated into bad camp, but McGoohan's direction keeps it on line with good performances all around." 52 It's a minor mystery as to why TV Guide would feature a review of the film, since it supposedly never aired on television to begin with.

As for the negative reviews, the U.K.-based Time Out website is particularly vicious, calling the film a "lame attempt" that is "hampered all the way by McGoohan's languorous direction, which lets each appalling moment of this uncomfortable hybrid of grade-school Shakespeare and grade-school religion sink wincingly in." 53

However, it is the write-up by Craig Butler from the All Movie Guide that saves the most hatred and venom for the film. This is the review most likely to be read by anyone today looking up general information on the film:

If anyone ever doubts that the '70s were a strange decade for cinema, they have only to watch Catch My Soul to find verification. In a way, it's emblematic of the decade, which encouraged a remarkable freedom of expression from its filmmakers; sometimes this resulted in highly individualistic masterpieces; other times it created dreck like Soul. Mind you, a lot of that dreck is highly watchable, in a "what could they have been thinking" kind of way, and Soul more than fits that bill. Director Patrick McGoohan had been involved (as an actor) in an imaginative and successful updating of Othello into the '50s jazz world (All Night Long), so perhaps he thought lightning would strike twice in moving it to a gospel show in the Southwest. He was terribly wrong. The re-setting is ham-handed and ridiculous, and the mixture of direct quotes from the play with contemporary slang is laughable. Laughable also describes every dramatic performance, as do horrible and unbelievable. (That said, some of the musical performances, especially from Richie Havens and Tony Joe White are quite good, and much of the music is worth hearing -- preferably on a turntable or 8-track, removed from the movie.) McGoohan's direction is labored, at best. Still, Soul is undeniably fascinating, a train wreck of a movie that inspires awe and that makes one appreciate a time when awful movies could be so bad in such an interesting way. 54

At this point, one begins to wonder what these current reviews are based upon. It's not like the reviewers had any recent access to the film. It's possible that the write-ups are cobbled together from negative reviews of the day, or might be based on memories of original reviewers who saw the film at the time of its release. Regardless, it's a bit disconcerting to read one critic's praise of McGoohan's direction, while someone else tears it apart.

A final odd legacy of Catch My Soul is that for such an obscure film, writers have always mentioned it in anything related to Patrick McGoohan or Richie Havens; be it a career retrospective of the former, or a concert appearance by the latter. Even in their obituaries from 2009 and 2013, respectively, Catch My Soul was duly mentioned as if it was common knowledge, and as if copies were readily available for anyone to see.

McGOOHAN SPEAKS

And what about the film's director? How did McGoohan feel about the experience years later? He said little about it, but the few quotes from him are enlightening. "I wish [Jerry Lee Lewis] had been in the film, then I could have had a lot of fun with it," he told Bill King in 1985 for Anglofile. "I did the best I could with it. I delivered my cut of it, some of which I thought was alright . . . [but that's] all there is to say about Catch My Soul. I believe it sank without a trace didn't it?" When King hinted that the film had a small cult following, McGoohan gruffly replied, "Hmph. I don't know how THAT became a cult." 55

Then, to Premiere magazine in 1995, he told more of the story. "[Catch My Soul is] how, after the hiatus that followed The Prisoner, I came back to the profession," he elaborated. "Unhappily, in the process of making the film, [Good] got religion -- Catholicism. He became a convert; he took the film and re-cut it. The editor warned me, and I asked for my name to be taken off it, but unhappily, that was not done. The result was a disaster. What's more, he added eighteen minutes of religious stuff. Ridiculous. But the music was good. Richie did one or two marvelous songs. Again, it's one of those typical show-business stories. Very sad." 56

Yet, perhaps McGoohan's feelings for the project were best summed up by what he bluntly told the Los Angeles Times in 1972, in the midst of directing the film: 57

"As far as I'm concerned, this is just another job."

The story of Catch

My Soul continues today in Part 2 HERE.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1. Booth, Rupert.

Not A Number: Patrick McGoohan -- A Life. Supernova Books, 2011.

2. Siegel, Ed. "Patrick McGoohan: The Prisoner Has Escaped; Now What?"

Boston Globe (January 13, 1985).

3. Castleman, Harry and Walter J. Podrazik. Harry And Wally's Favorite TV Shows.

Prentice Hall Press, 1989.

4. Kilday, Gregg. "Madness, Shakespeare and Manson Join Hands in Santa

Fe." Los Angeles Times (November 26, 1972).

5. Burman, Barbara. "Stratford-on-the-Rio-Grande." The New Mexican

(November 19, 1972).

6. Smith, Cecil. "'Catch My Soul' Rocks the Ahmanson Theatre." Los

Angeles Times (March 7, 1968).

7. Kilday.

8. Greig, Simon. "Catch My Soul" review. Films and Filming, December

1973.

9. Kilday.

10. Kilday.

11. King, Bill. "Patrick McGoohan: An Interview With The Man Behind 'The

Prisoner.'" Anglofile Magazine, 1988.

12. Cashin, Fergus and Chris Kenworthy. Jack Good Interview. The Sun [U.K.]

(November 17, 1973).

13. Kilday.

14. Furnival, Andrew. "Tony Joe: Exception In His Own Right." Sounds

Magazine (September 29, 1973).

15. Burman.

16. Freedland, Nat. "TV Producer Injects Studio Tricks In Rock 'Othello.'"

Billboard (November 18, 1972).

17. Burman.

18. Kilday.

19. Kilday.

20. Furnival.

21. Kilday.

22. Kilday.

23. http://douglasmagnus.net/?p=1030

24. Magnus, Douglas. Phone conversation with the author. June 8, 2013.

25. Magnus (as above).

26. Freedland.

27. Sharpe, Tom. "Satanic Bomb." The Santa Fe New Mexican (April 13,

2003).

28. Burman.

29. Burman.

30. Beck, Marilyn. "Othello Rocks In 'Catch My Soul.'" Palm Beach

Post (July 17, 1973).

31. Siegel.

32. Beck.

33. Greig.

34. Noth, Pierre-Rene. "Sounds of The Times." Milwaukee Journal (January

16, 1974).

35. Canby, Vincent. "'Othello' Loseth." New York Times (March 23,

1974).

36. Crist, Judith. "More Vague Than Nouvelle." New York Magazine (March

25, 1974).

37. Canby, Vincent. "'Catch My Soul' Is Funny." Atlanta Constitution

(March 30, 1974).

38. Kelly, Kevin. "Films Shellack Two Standards." Boston Globe (May

16, 1974).

39. Whitehorn, Ethel. "Catch My Soul" Review. PTA Magazine, June 1974.

40. Variety editors. "Catch My Soul" Review. Variety (March 20, 1974).

41. Sharpe.

42. Moorehead, Jim. "Film Modern Day Hamlet." Evening Independent

(February 20, 1976).

43. Herman, Fred. "Woody Guthrie Would Have Liked It." The Modesto

Bee (March 31, 1977).

44. Limbacher, James L. Feature Films on 8mm, 16mm, and Videotape (7th Ed.).

R.R. Bowker Company, 1982.

45. Albright, Rick. "Not Crazy." Merced Sun-Star (August 9, 1983).

46. IMDb & Wikipedia entries for Metromedia.

47. Metromedia discography (http://www.bsnpubs.com/new/metromedia.pdf)

48. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metromedia)

49. Epstein, Norrie. The Friendly Shakespeare. Viking, 1993.

50. Kilday.

51. Shock Cinema on Mary's Incredible Dream (http://www.shockcinemamagazine.com/marys.html)

52. TV Guide Review (http://movies.tvguide.com/catch-my-soul/review/110529)

53. Time Out Review (http://www.timeout.com/london/film/catch-my-soul)

54. Butler, Craig. All Movie Guide Review (http://www.allmovie.com/movie/catch-my-soul-v86841/review)

55. King.

56. Katelan, Jean-Yves. Patrick McGoohan Interview. Premiere Magazine [France],

October 1995.

57. Kilday.